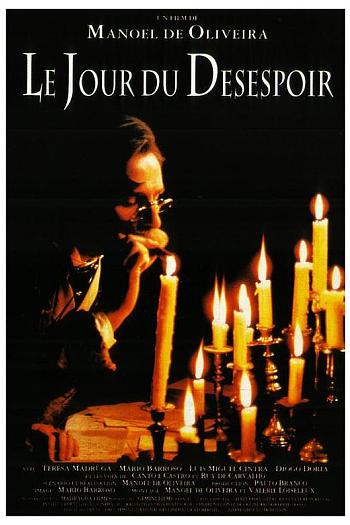

绝望的一天

| 导演: | 曼努埃尔·德·奥利维拉 |

| 编剧: | 曼努埃尔·德·奥利维拉 |

| 主演: | 特丽莎·马德鲁加 马里奥·巴罗索 路易斯·米格尔·辛特拉 迪奥哥·多瑞亚 Canto e Castro 鲁伊·德·卡瓦略 Nuno Melo |

| 制片国家/地区: | 葡萄牙 / 法国 |

| 类型: | 剧情 / 传记 |

| 语言: | 葡萄牙语 |

| 年代: | 1992 |

| 片长: | 75分钟 |

| 豆瓣评分: | 0 |

| IMDB: | 0 |

| 影伴评分: | 0 |

剧情简介

In 1992 Oliveira made O Dia do Desespero, which deals with the last days and suicide of Romantic novelist Camilo Castelo Branco and is based largely on the writer's letters. Most of it was filmed in the house where Castelo Branco in fact committed suicide. The film opens, midway through the credits, with a 50-second static shot of a pen-and-ink portrait of the writer. Other por... (展开全部)

In 1992 Oliveira made O Dia do Desespero, which deals with the last days and suicide of Romantic novelist Camilo Castelo Branco and is based largely on the writer's letters. Most of it was filmed in the house where Castelo Branco in fact committed suicide. The film opens, midway through the credits, with a 50-second static shot of a pen-and-ink portrait of the writer. Other portraits, always shot with a static camera, punctuate the film's narrative, lending it a documentary tone from the outset.

The spectator might expect, at this point, that the “story” will now begin. However, the man seated at the desk stands up, faces the camera, and introduces himself as the actor Mário Barroso, who will be playing the role of Camilo Castelo Branco (and who played Castelo Branco in the earlier Francisca), and offers information about the writer. A bit later in the film, Ana Madruga, the actress who plays Castelo Branco's companion Ana Plácido, does the same thing, at the same time briefly serving as a “guide” to the Castelo Branco museum where the film was shot. Despite the existence of these ostensibly “documentary” elements – the house, the portraits, the actors presenting themselves as such – O Dia de Desespero, Oliveira insists, is a fiction film, but it is one that refuses to deceive the spectator (in Baecque and Parsi, 56) by pretending to be what it is not. In O Dia de Desespero and other films, Manoel de Oliveira questions the ontological status of such terms as “fiction” and “documentary” and challenges, through the pursuit of his own cinematic vision, some of the filmic and narrative conventions that have come to dominate mainstream commercial cinema. His films also challenge the spectator to think about, rather than passively accept, that which is shown on the screen.

In 1992 Oliveira made O Dia do Desespero, which deals with the last days and suicide of Romantic novelist Camilo Castelo Branco and is based largely on the writer's letters. Most of it was filmed in the house where Castelo Branco in fact committed suicide. The film opens, midway through the credits, with a 50-second static shot of a pen-and-ink portrait of the writer. Other por... (展开全部)

In 1992 Oliveira made O Dia do Desespero, which deals with the last days and suicide of Romantic novelist Camilo Castelo Branco and is based largely on the writer's letters. Most of it was filmed in the house where Castelo Branco in fact committed suicide. The film opens, midway through the credits, with a 50-second static shot of a pen-and-ink portrait of the writer. Other portraits, always shot with a static camera, punctuate the film's narrative, lending it a documentary tone from the outset.

The spectator might expect, at this point, that the “story” will now begin. However, the man seated at the desk stands up, faces the camera, and introduces himself as the actor Mário Barroso, who will be playing the role of Camilo Castelo Branco (and who played Castelo Branco in the earlier Francisca), and offers information about the writer. A bit later in the film, Ana Madruga, the actress who plays Castelo Branco's companion Ana Plácido, does the same thing, at the same time briefly serving as a “guide” to the Castelo Branco museum where the film was shot. Despite the existence of these ostensibly “documentary” elements – the house, the portraits, the actors presenting themselves as such – O Dia de Desespero, Oliveira insists, is a fiction film, but it is one that refuses to deceive the spectator (in Baecque and Parsi, 56) by pretending to be what it is not. In O Dia de Desespero and other films, Manoel de Oliveira questions the ontological status of such terms as “fiction” and “documentary” and challenges, through the pursuit of his own cinematic vision, some of the filmic and narrative conventions that have come to dominate mainstream commercial cinema. His films also challenge the spectator to think about, rather than passively accept, that which is shown on the screen.